Keeping my post-prandial glucose low protects me from type 2 diabetes and CVD doesn't it?

Let's think about cause vs marker

In the previous articles I described how prolonged hyperglycaemic exposure is related to negative health outcomes including things like cardiovascular disease. And I hope it was evident from the post on prediabetes that there is even some uncertainty about the exact role that the prolonged hyperglycaemia observed in the prediabetic state plays in health and disease. Now let’s move onto glucose excursions in normoglycaemia.

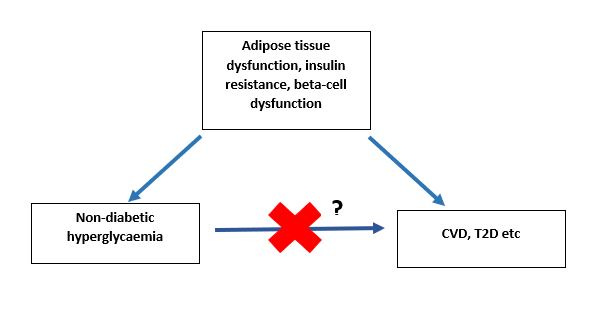

In the post I want us to think about whether glucose is a cause of or a marker for disease risk.

I think one of the key points to remember when we are relating glucose concentrations to an outcome is to think about whether glucose is a cause or whether glucose is merely a marker for damage underneath, and it is the damage underneath that is causing negative health outcomes.

Let me explain.

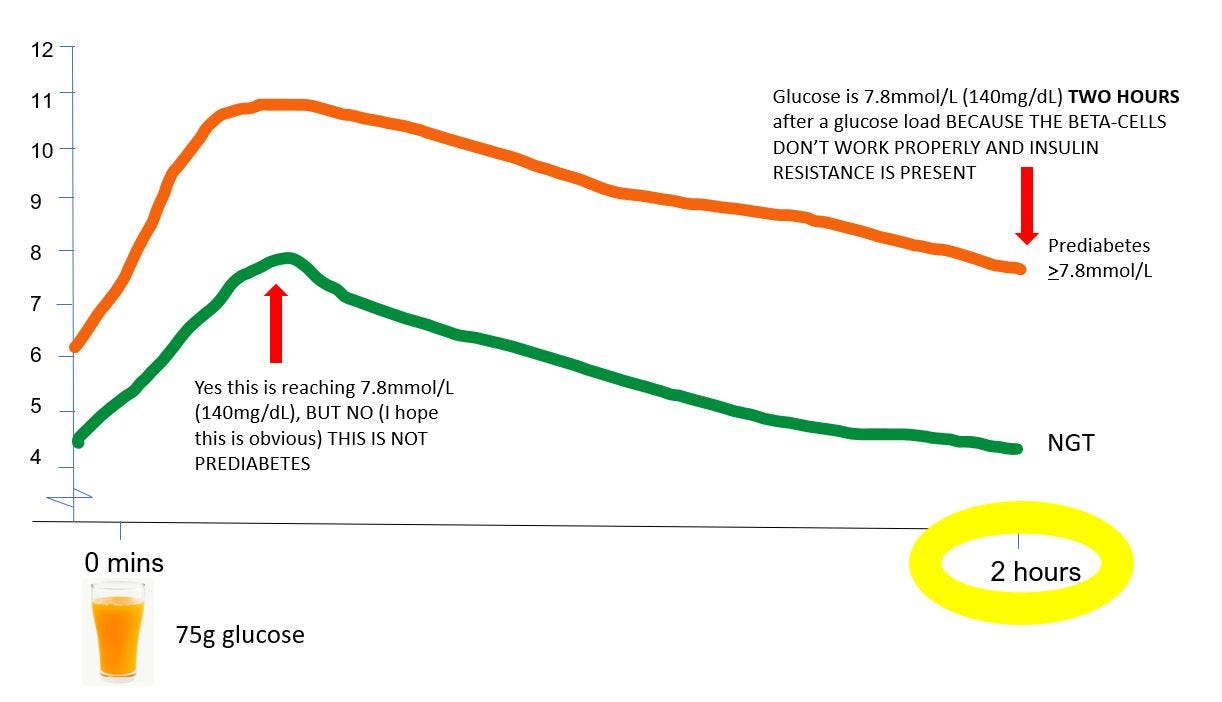

In prediabetes and type 2 diabetes, the reason people have elevated blood glucose at eg 30 (and 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes…. after a glucose load is because 1) the beta cells aren't working properly, and 2) they have insulin resistance, either in the liver or in the muscles, or both.

Although insulin resistance can be broadly described as insulin not doing its job properly, at a molecular level it's actually a lot more complicated, and not completely understood. Insulin basically works through relatively complex signalling cascades, and when there are impairments along any part of the signalling pathway, it can impair the actions of insulin. And insulin is not just involved in regulation of glucose metabolism, it's also involved in amino acid, lipid metabolism, vascular function and other biological processes.

So, if insulin resistance [impairments in the insulin signalling pathway] is causing elevated blood glucose, it may also be causing impairment and damage to other aspects of cardiovascular function. In other words, it might not be elevated glucose per se which is causing the elevated risk of CVD, it’s the underlying metabolic dysfunction [which causes raised glucose excursions] which is causing the increased CVD risk*.

Here you can see the problem with eating with the sole aim of lowering your glucose excursions- particularly in people with normoglycaemia who are worried about glucose spikes. At best, you might be eating in such a way that makes zero difference to your actual risk of disease (and maybe unnecessarily depriving yourself of foods you enjoy!) Or you could even be making the underlying pathophysiology worse!

Likewise, think about the relationship that’s been observed between elevated 30-minute glucose and type 2 diabetes. People often see this data and say “well people who have a high glucose excursions are at higher risk of type 2 diabetes, therefore if I can keep my glucose excursions low, I will reduce my risk of getting type 2 diabetes”. Again, not so fast. Why do people have elevated 30 minute glucose? Their beta-cells don’t work properly (and they’ll have some insulin resistance). And what is the primary defect that distinguishes people with type 2 diabetes (about 6-10% of the population) from those who just have insulin resistance (about 60-65% of the population)? Their beta-cells don’t work properly. So people who have have impaired beta-cell function (which causes an elevated 30-minute glucose) have a higher risk of type 2 diabetes? No shit.

If you’re thinking “wait, there is data showing that people with an elevated 30 minute glucose BUT a normal 2-hour glucose have a high risk of developing type 2 diabetes, so glucose peaks do matter!”, this is where understanding of the pathophysiology of prediabetes comes in.

I mentioned that people with isolated impaired fasting glucose (a type of prediabetes) have slightly different presentation of insulin resistance to people with impaired glucose tolerance (another type of prediabetes). They also have differences in insulin secretion which likely explain this presentation of high initial glucose which then goes back to normal by 2 hours.

There are basically two phases of insulin secretion** after a meal/carb load in healthy people: in the first/early phase, the pancreas releases a large amount of insulin very quickly to reduce the glucose rise, and start bringing it down. The second (late) phase then releases enough insulin to mop up the rest of the excess glucose that’s hanging around. People with isolated-IFG have an impaired first (early) phase insulin response to a glucose rise after a meal/carb load, but an intact second (late) phase insulin response.

So in IFG what you see is a large peak of glucose early on (because the first/early phase insulin response doesn’t work properly). But then you get an exaggerated second/late phase insulin response (the beta-cells panic a bit because they recognise glucose is much higher than it should be) which then brings glucose crashing back down again - and is very often much lower than the fasting glucose was.

So, an elevated 30 minute glucose and a normal 120 minute glucose may be explained by existing underlying pathophysiology (which itself causes type 2 diabetes) - and does not necessarily mean that it’s the high glucose peak per se which is causing the increased risk of type 2 diabetes/CVD/anything else.

*Note that here I am referring to non-diabetic concentrations of glucose. In type 1 and type 2 diabetes where blood glucose concentrations are elevated above 11.1mmol/L (200mg/dL) for long periods of time, the hyperglycaemia is a direct cause of damage, eg retinopathy.

**the terminology used here is not 100% precise because you really only see the two phases during a hyperglycaemic clamp type of study where you infuse glucose into a vein. However, the phenomenon of the beta-cell responding in a phasic way to manage glucose concentrations post-carb load is there even if we can’t observe visual differences in insulin concentration post-prandially.

So does this mean it's ok to snack on unprocessed, low-glycemic foods in between meals for those with normal post-prandial glycemia? So as long as I'm not insulin-resistant, or, have beta-cell dysfunction, it really doesn't matter how many times I spike my glucose during a day, as long as I'm eating "healthy" food?

Is this correct?

Thank you very much for your posts; they are absolutely amazing! To ensure I understand correctly, can we infer from the text that pre-diabetes is caused by insulin resistance and/or improper functioning of beta cells? What role does diet play in this? Can diet lead to pre-diabetes, perhaps by increasing insulin resistance and impairing beta cell function?

For example, imagine someone starts a new habit: they eat two cookies every hour from 8 am to 3 pm., totalling 14 cookies a day. At the same time, they reduce their physical activity. If this person continues this habit for a year, and their HbA1c level is measured before and after, would we see an increase in their HbA1c level? They will have more sugar spikes but from your text, should we infer that a healthy person would produce insulin and therefore the body would respond to this sugar spikes lowering it? Could the higher sugar intake and lack of activity have increased insulin resistance and worsened beta cell function? How do insulin resistance and beta-cells atrophy happen and what can be done to avoid it? Thank you!