iNfLaMmaTiOn

Fire!

Why do healthcare professionals and scientists care about inflammation? Because inflammatory factors such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are associated with many diseases including type 2 diabetes, arthritis and even depression and anxiety. While previously considered to be just a response to pathogens and injury - it’s now understood that inflammation may also arise from metabolic stress. Nutrition is a proximal modulator of the latter, so it’s natural that people think “ah ha, I can reduce inflammation with diet”.

Can you? TL/DR: You can, and as far as we know it’s by losing weight (if you are overweight) and having a plant-rich diet.

For a critical review of the rest of the stuff that you’ll see on YouTube like avoiding glucose spikes, reducing carbs, and not snacking, read on.

First of all, what are inflammatory factors?

Inflammatory factors are basically the chemicals, proteins and molecules which make up the immune response, and can be used as markers of the amount of inflammation in the body. These include cytokines, chemokines and acute-phase proteins. The ones that are the most well-studied AFAIK are C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha). But there are tons of them.

The number of potential inflammatory markers really matters when we consider studies which examine them. As complex biological factors, their concentration in the body probably changes constantly at any given time. So if you are measuring a lot of them in one study and one changes, is it a type 1 error (false positive) borne from multiple comparisons or a legit finding? And if one inflammatory marker goes down and one goes up, what does this mean clinically? I don’t think anyone knows for sure, at least for most of these factors. And what about when studies only measure a limited number of them? What meaning does a small change in IL-6 have, when we don’t have data on what the rest of the markers did?

It’s also worth mentioning that although many inflammatory factors are associated with the development of diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease, the production of these inflammatory markers increases in these conditions. So establishing a causal relationship is challenging.

This context is important when we consider the promotion of stuff on YouTube (hello the Zoe Science and Nutrition Podcast), instagram and probably TikTok based on how they affect iNflAmMaTIoN.

Let’s dive in.

Acute versus chronic (basal?)

We get a rise in some inflammatory markers when we eat, just as we get an increase in glucose, triglycerides, free-fatty acids, insulin and body temperature.

An acute rise in a molecule or hormone is not the same thing as chronic elevation. I explained why in this series about glucose, and the same is probably true for inflammation. To my knowledge, the studies we have showing a relationship between inflammatory markers and disease look at fasting measures of inflammation. If your fasting markers are high there is a good chance they are elevated 24/7. Some might look at post-prandial rises in inflammatory markers, BUT unless they adjust for basal, they are probably just looking at people whose inflammatory markers are high in the fasting (basal) condition.

This distinction between meal-related and basal (chronic) inflammation is critical when we talk about diet.

For example, people who have a lot of carb (not talking about quality here, just the amount), will have frequent, acute rises in their blood glucose. If acute rises in glucose cause inflammation to a degree that’s problematic, we would expect to see a relationship between the glycaemic load of the diet and inflammatory markers, right? But we don’t. Some studies find a relationship between the glycaemic index and inflammation, but this might just be due to the “extra-glycaemic” effects of carbohydrates (ie, colonic fermentation of fibre, not glucose response per se).

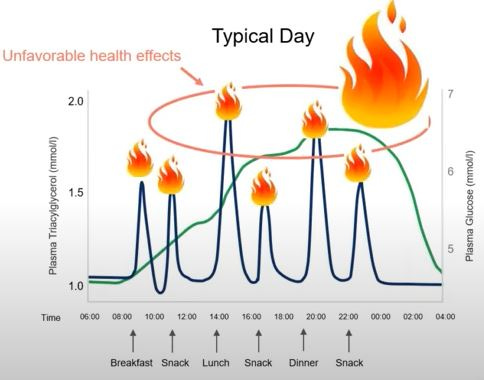

Well, what about having frequent meals and snacks as per the below slide, such that you’re basically in the post-prandial state most of the day?:

The slide comes from a talk by a member of the Zoe scientific team who makes the case that post-prandial glucose and fat excursions cause an inflammatory response, and when people eat frequently it means they are constantly in this kind of “inflammatory state”. This is a perfectly reasonable hypothesis. But a simple review of the literature would suggest this probably isn’t true.

In the NHANES data set, one additional snack or meal per day was associated with an 8% reduction in CRP.

This crossover trial shows no difference in inflammatory markers when people had one meal a day compared to three meals a day.

Now, I am not saying having frequent meals is a good or a bad thing. Nor am I claiming that eating more frequently lowers inflammation. But I am pointing that the data does not suggest that spending a lot of time in the post-prandial state causes inflammation.

Let’s review other specific claims in more depth:

You need to avoid glucose spikes!

CGM companies claim that one of the reasons people without diabetes should pay attention to their glucose excursions is because high glucose excursions cause inflammation. And inflammation then leads to all sorts of nasties like endothelial/vascular dysfunction*.

There is definitely evidence that the magnitude and duration of hyperglycaemia and oscillating glucose you see in diabetes is linked to inflammation/oxidative stress and endothelial/vascular dysfunction.

I have never seen a solid study that the limited rises or peaks and troughs we see in normoglycaemia (let’s define this as HbA1c <5.6% just to put a number on it) influence these things in any meaningful way.

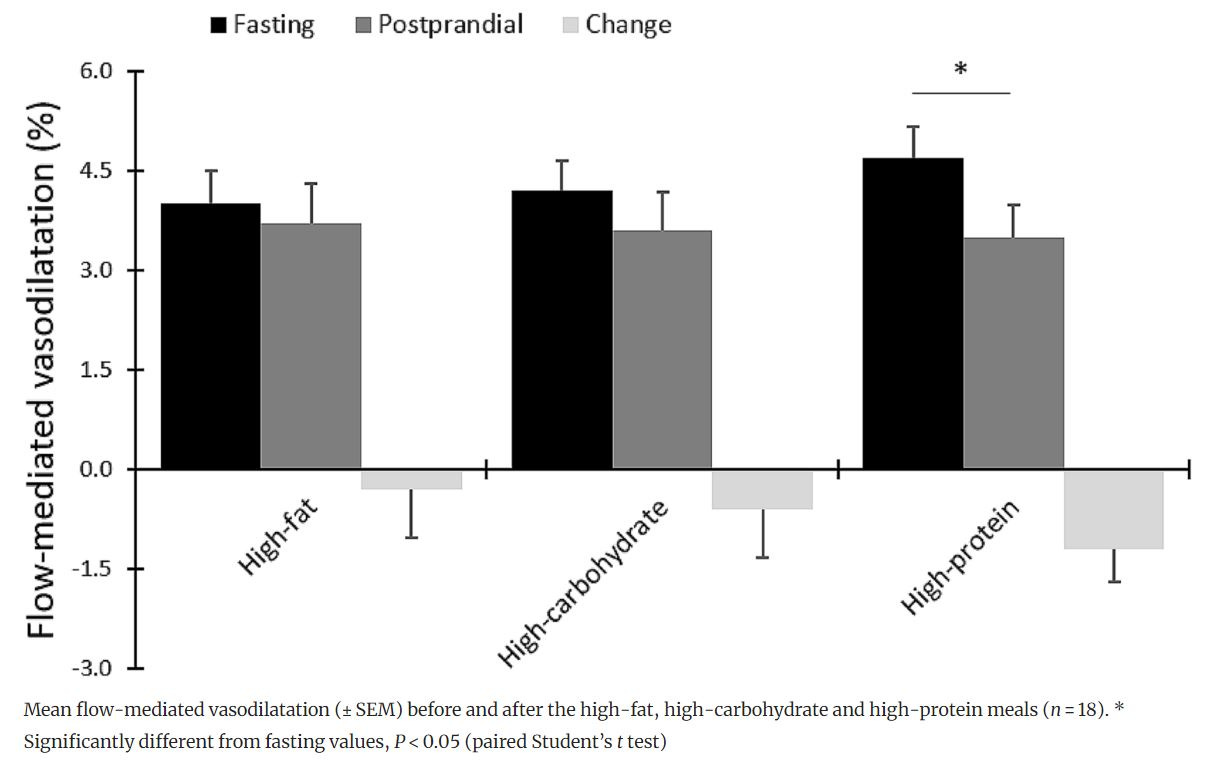

For example, although many studies do show an association between the glucose rise following an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and impairment in flow-mediated dilation (a measure of vascular function) these studies have important limitations because they don’t have a control group. If you play devil’s advocate you might say, “well, carbohydrate is energy, so you’re putting energy into the body. Maybe putting energy from any source into the body would cause the same thing, and the apparent “impairment” is just the response we have to eating?” This has been tested in this study that compared three different meals, each differing in carb, fat and protein content but each providing the same amount of calories. They did see a large and clinically relevant reduction in glucose excursions in the low-carb and high-protein groups compared to the high-carb group, but did this have any effect on vascular function? No:

Likewise, this study compared the inflammatory responses to a high-fat meal, a high-carbohydrate meal and a Mediterranean diet meal (MED) in people at high cardiometabolic risk (BMI ~ 30 and mean age of 70 years) and didn’t see any meal-induced differences in inflammatory factors, despite there being differences in the glucose response. So in terms of glycaemic excursions, there is not much evidence for this having any practical relevance in terms of the inflammatory response and the pathophysiological sequelae. In fact, many inflammatory markers might not change at all acutely in response to meals.

Looking longer term, we also don’t see greater improvements in vascular function when we compare a 6-week low-carb with 6-week low-fat diets. And there have been no conclusive findings on the effect of long-term diets differing in macronutrients on inflammatory markers anyway.

In summary, there is little evidence that acute glycaemic responses to meals (in people without diabetes) are relevant in terms of inflammation and its pathophysiological consequences.

How do I reduce chronic inflammation?

The best evidence we have is for the following 3 things:

Weight loss (for people who have overweight/obesity). Adipose tissue releases inflammatory factors so this isn’t a huge surprise.

Exercise

Get more plants and fibre, hahaha. The microbiome may well play an important role in this. Feed it lots of fibres and you’ll probably get a colonic environment better at fighting pathogens. If fewer pathogens enter the bloodstream, you reduce inflammatory markers in the blood.

Bottom Line

Be wary of hand-waving, poorly-defined and reductionist claims about things like iNfLaMaTiOn. And also remember lots of things go up after a meal because we have to metabolise food:

Glucose

Lipids

Insulin

Inflammatory factors

Temperature

People who want to sell you devices that measure your acute responses to meals have a vested interest in scaring you into thinking convincing you that these acute responses are critical for your health**.

Anyway, this is probably my last post before Christmas so let me wish you a very happy Christmas and I hope you don’t get a CGM from Santa BAHAHAHAHA. (And also sorry for the delay in getting this one out - it’s been GRANT SUBMISSION season).

*Endothelial/vascular function is measured clinically using standardised testing and is a useful way of understanding how healthy the blood vessels are.

**Unless you have (or are suspected of having) a clinical condition like diabetes or hypercholesterolaemia I don’t think the data we have currently suggests there is much biological value in measuring and worrying about these acute meal-related factors above standardised clinical criteria.

Merry Christmas Dr. Guess, another great post as usual.

Good food for thought and excellent practical advice. I shall follow.