A paper came out a few weeks ago by Kevin Hall et al on an ultra-processed food (UPF) and the dopamine response, and I wanted to touch on it and summarise where I think the literature sits now with regard to UPFs. I am going to focus on obesity and its associated cardiometabolic diseases in this post, but just FYI there is a big trial coming out soon on emulsifiers and gastrointestinal health so I’ll cover that for sure.

Ultra-processed foods and food addiction

With regards to dopamine, the hypothesis is that UPF consumption causes an excessive dopamine response (which makes us feel really good). In response to the high dopamine, our dopamine receptors downregulate. So the next time we want that dopamine “high”, we need more of the stimulus, in this case - the UPF. It’s a perfectly reasonable hypothesis.

This new trial tested the dopamine response to a UPF milkshake using PET scans. The investigators also explored whether people with obesity had a different dopamine response to lean individuals. The thinking here is that “well, since UPF consumption is a significant driver of obesity, then people with obesity should have a lower dopamine response because they have become “addicted” to UPFs”.

The investigators found:

No significant mean dopamine response to ultra-processed milkshakes

No significant relationship between dopamine responses and adiposity.

So, this study did not find that a UPF food (in this case a milkshake) alters the dopamine reward pathway. Of course, this doesn’t mean “case closed” at all. Firstly, there are multiple neurochemical pathways through which a food or ingredient could have addictive potential and just because this paper didn’t find that dopamine was the mechanistic “culprit”, doesn’t mean there couldn’t be others. In addition, this study was carried out in people without a history of eating disorders, and it’s perfectly feasible that responses might be different in this clinical group.

But actually, I’m pretty skeptical that the “drug-like” addictiveness of these foods could play a big role in us overconsuming them simply because a large proportion - possibly nearly all - of the “overconsumption” can currently be explained by other mechanisms.

Why do UPFs cause us to overeat?

If you’ve been reading my blog for a while, feel free to skip down to “Which of these properties is the most important” as I am quickly going to reiterate the points I have made in previous blogs.

Firstly let me re-iterate my position that whether a food causes us to overeat or not cannot be defined by how processed it is. It’s certainly true that UPFs are more likely (in fact far more likely) to have the properties that cause us to overeat, but ultraprocessing per se does not necessarily mean that a food is obesogenic.

So what are these properties? Let’s review.

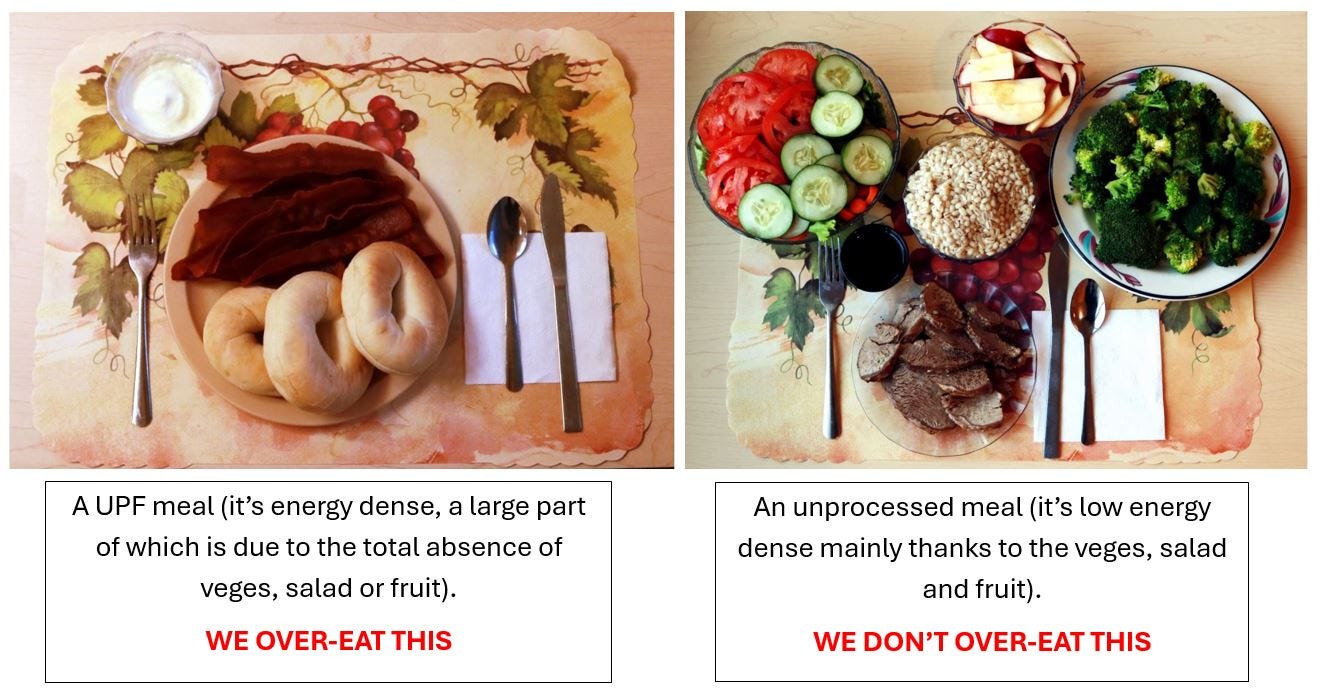

Energy density

Energy density refers to the calories per gram of food*. Basically we think that we overeat them simply because when we are eating foods with loads of calories per bite, we can consume a high number of calories before our appetite systems can even register we’ve consumed those calories. Ultra-processed foods and meals are more likely to be energy dense.

In this piece I describe how the amount of calories we overeat on a UPF diet closely matches the amount of calories we overeat on an energy-dense diet.

(But remember - if energy density is the property that’s causing us to overeat, energy-dense home-made foods would do exactly the same thing).

Hyper-palatability

Another of the properties is hyper-palatability - this is a hard-to-define concept that basically means that there are particular tastes/nutritional combinations that human beings really, really like and tend to eat more of. Combinations that have been identified as hyper-palatable are 1) Fat and sodium (delish creamy sauces), 2) fat and sugar (doughnuts/ice cream) 3) carbohydrate and sodium (fries, crisps). And by the way it seems like there’s a sweet-spot of fat vs carb, carb vs salt etc - such that a certain percentage of each is particularly delicious.

As an example of these hyper-palatable combinations, this crossover trial tested whether adding more salt to meals caused people to eat more of the meal. They tested two different meals in this study, and each was either low-salt (LS) vs high-salt (HS):

Pasta with tomato sauce (low-fat (LF))

Pasta with a cream sauce (high-fat (HF)),

They found that participants ate more of both the low-fat and high-fat pasta meals if the sauce was saltier! (And since the high-fat meal was also more energy dense, the combination of high-fat and high-salt was the most obesogenic).

So yeah, we tend to stuff ourselves with high-fat, high-salt foods. An unprocessed “clean” meal of steak with butter and salt on? We’ll probably overeat that. Especially if it’s the type you get in Argentina that you can cut through with a butter knife…..

Hardness vs softness

We tend to eat soft foods more quickly. This very neat study demonstrated that people ate softer foods at a much faster rate, and consumed more calories, than when they ate hard foods. Notably, whether a food was soft versus hard had a greater impact on the eating rate and calorie intake than whether the food was processed or not.

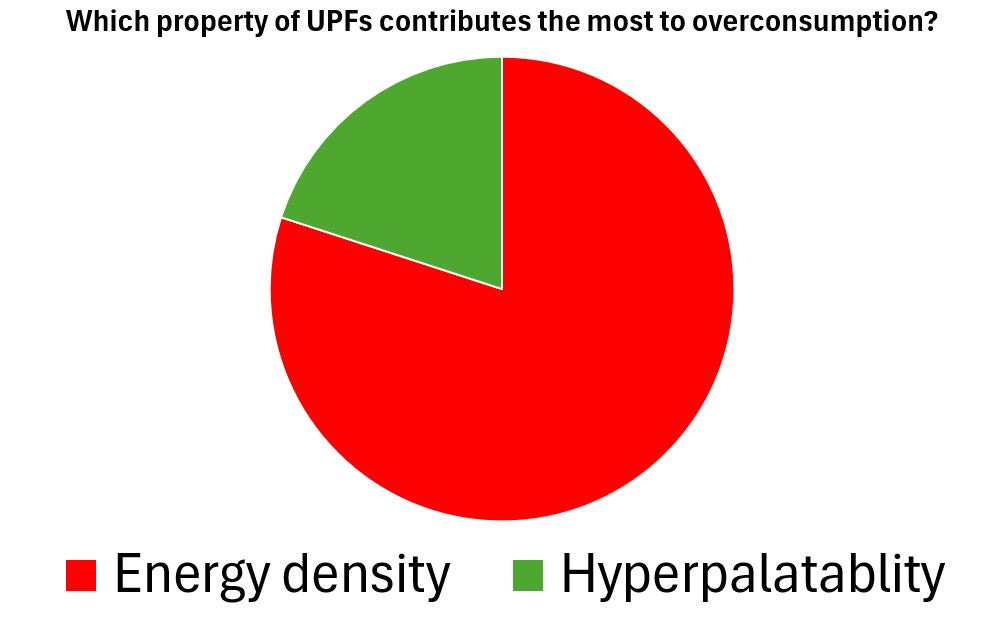

Which of these properties is most important?

Kevin Hall recently presented the interim data from a new trial of his. It’s an incredibly cool design that tested four groups:

Minimally processed (low energy-dense and low in hyper-palatable foods).

UPF - high-energy dense, high in hyper-palatable foods.

UPF - high-energy dense, low in hyper-palatable foods.

UPF - low-energy dense, low in hyper-palatable foods.

This design is incredibly cool because it tests the effect of high energy-density + /- hyper-palatability under standardised conditions for the first time. This type of design helps to assess the relative contribution of each property to overconsumption.

His interim data suggests that energy density is driving the overwhelming majority of additional calories that people eat from UPF diets. The high-energy dense, hyper-palatable group ate about 1000kcal more than the minimally-processed group. The high-energy dense, low in hyper-palatable foods group ate about 800kcal more. So it seems from this data that energy-density is explaining around 80% of the obesogenic effect of UPF diets.

Oh and by the way, the low energy-dense, low in hyper-palatable foods UPF diet caused people to consume about 170kcal extra compared to the minimally-processed diet. This difference is within the margin of error - and was not statistically significant. This suggests that we might be able to develop UPF foods which don’t cause over-eating. When the full study is published I will write about it more, once we can see what meals people were given.

But wait, UPFs might not be off the hook yet……

While we could potentially be excited that a UPF diet which is not energy-dense nor hyper-palatable does not seem to cause weight gain, this doesn’t mean we can relax completely.

Because Kevin’s data from this new trial found that even though the non-energy dense and non-hyper-palatable UPF diet didn’t cause overconsumption, all the UPF diets caused unfavourable changes in body composition compared to the minimally processed diet. People gained fat and lost lean mass. Not good.

What’s going on?

There is existing data showing that fibre (particularly, viscous, fermentable fibres) helps increase fat oxidation, and also favourably alters body composition. Kevin’s studies used Nutrisource which is partially-hydrolysed guar gum - the hydrolysis makes it water soluble, and reduces the viscosity.

So the unfavourable body composition caused by UPF diets might reflect the lack of viscous fibres in the diet.

However, we should not assume this. For example, the molecular and cellular decomposition of ingredients like grains or legumes has been implicated in disruption of the microbiome. So we don’t know for sure whether having UPF foods is fine as long as a threshold of other ingredients (whole veges, nuts seeds etc) is met. We do need to understand this more precisely.

This is also important to find out because it if it just a lack of intact grains, whole fruits and veges etc, then an unprocessed meals of rice and meat might do the same? Or potatoes and fish?

Why does all this waffling about mechanisms matter?

We need to understand these mechanisms to get our nutrition and food policy right

We cannot educate our way out of the obesity crisis because knowledge does not meaningfully change behaviour. We have to change our food environment so that healthy foods and meals are more readily available and cheaper than unhealthy options.

For sure we know enough right now that we should be (sorry libertarians) taking action such as putting taxes on the high in saturated fat, sugar, and salt foods (the so-called HFSS group, and recognise that these will be energy-dense and or hyperpalatable), and removing them from schools like other countries have done. In the US about 75% of UPFs are HFSS, and it’s around 55% in the UK.

So what about the UPFs that don’t fit into HFSS? This includes some yoghurts, cereals, breads, plant-based milks and meat and artificially -sweetened beverages. If they’re not energy-dense or hyper-palatable, then they might well be perfectly fine! Processing can also make foods cheaper, last longer (so reduces food waste), convenient (so for those of us that aren’t really kitchen people, we can eat healthily without having to spend too much time cooking) and more. And if a company makes a food product which meets people’s tastes and needs and doesn’t cause harm, and makes a profit while doing so, and can employee people and pay money into the treasury and/or shareholders…. surely this is a net societal win?.

Oh, and if we find that these non-HFSS-UPFs may disrupt our health in other ways, we can use policy tools to either mandate removal of certain ingredients, or to modify the food structure.

I haven’t touched on additives in this piece as it’s a complex area which can’t be summarised succinctly. The effect of additives on health is a poorly researched area that we need to understand better. And if new research shows additives either alone or in combination look suspect, we can remove them from the food supply.

So my position is that by understanding what the properties are within UPFs which causes us to over-consume them - or cause us harm in other ways - we can then enact precise science-backed food policies which are more likely to be effective. For example, (I’m spitballing here as a non-policy person so hear my crazy ideas out): if we put a 10% tax on ready-meals with an energy density above 2, it might a) Lower the purchase and consumption of that product; b) encourage the manufacturer to modify the recipe to make it less energy dense. And I would use all tax income to subsidise fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes.

Sorry everyone, that was a long one.

*We don’t use volume in this definition because it’s really hard to measure - and keep standardised - ie the volume of popcorn might vary depending on whether it’s just been poured or not - and wheat science likes is consistency and standardisation to the extent possible.

Disclaimer

As a dietitian, and not a medical doctor, I am not qualified to diagnose any health conditions.

Fascinating, thank you. I also think part of the UPF problem is not the food itself but it's absolute availability. Food is everywhere, eating is now leisure, almost a hobby. Meals used to be meat and two veg and pudding (not dessert) for Sundays. Confectionery was only available from sweet shops and paper shops not everywhere as now. There seems to be a Greggs every 250 metres.

Thank you for another great article.