Why I laugh at most microbiome trials

The microbiome is the 21st century’s Human Genome Project. People are excited about it in the way that people often are about anything new. In some ways it is a significant advancement in our understanding of nutrition and health, but as always people take it too far and honestly think this new field of nutrition is going to solve all our problems: “we don’t have to fix our living environments, transport, food systems because we just need to fix our microbiomes!” or “conventional dietary guidelines have failed because they’re not personalised to people’s microbiomes!”.

Now there is some really cool microbiome research being done*- albeit hypothesis generating (and that’s ok as long as investigators acknowledge that). But at the moment 95% of microbiome trials have so many flaws they basically aren’t and can’t tell us anything new.

Here’s why:

“[X] changed the microbiome!” has basically no meaning

Loads of trials report that a diet or ingredient “changed the microbiome”. What’s the problem with that? The microbiome changes all the time. Below is one of my favourite figures. It’s from a rodent study and the figure shows the changes in the individual species in the control group (RED LINES) who literally just carried on doing what they were doing before the study started and the intervention group (BLACK LINES) who were given sucralose over a 6 month period. If the figure wasn’t labelled, I don’t think you would be able to tell which was the intervention group.

Now you might be thinking “ah but it’s not just any changes in bacteria we care about, it’s changes in the numbers of “bad bacteria”. Oh, ok then. What are the “bad” bacteria? How do we know they’re “bad”?

HAAHAHAHAHHAHAHAA.

We can’t be precise about what “good” and “bad” bacteria are.

The data we have on what a “healthy microbiome” should like like comes from association studies. We look at people with disease and people without disease and look at what species etc are associated with both**. Now one of the problems with doing this is that diseases can alter the microbiome (eg really high glucose can alter the growth of certain microbes, and medications you might take for some diseases can too) - so it can be hard to know whether it was the bad bacteria that caused the disease or vice versa (and of course this is deeply relevant if we want to improve or alter our microbiome to prevent disease).

So we really have no idea what an increase in one or another specific bacteria or species means in terms of the health of the microbiome or our overall health.

All we can reasonably claim is that there are trends in the proportions of certain types of microbes that are associated with certain health conditions. Fine, if that’s the best we can do, so be it. So surely then, when you design a trial aiming to improve the microbiome, you at least try to specify the impact your diet or supplement has on the proportions of specific groups of microbes, yes? And you define this ahead of time?

HAHAHAHAHA.

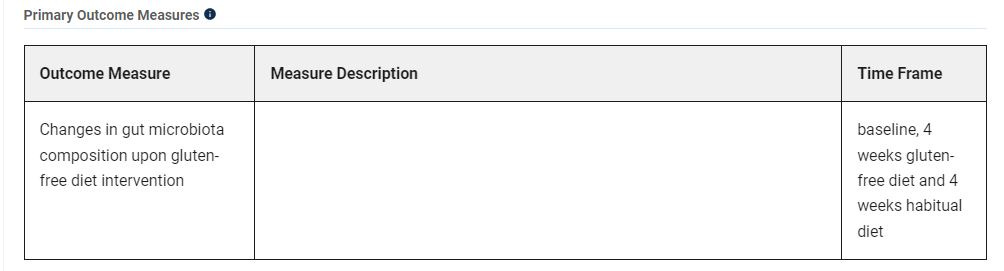

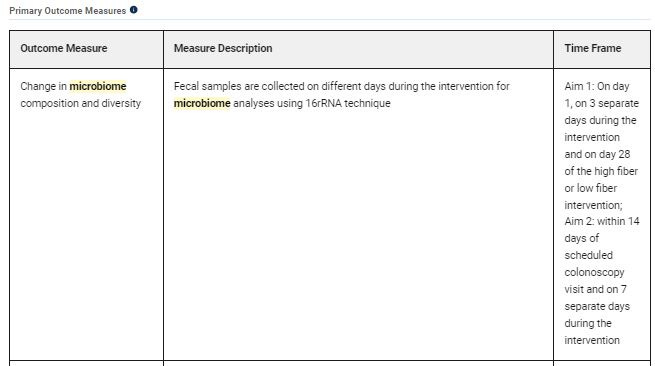

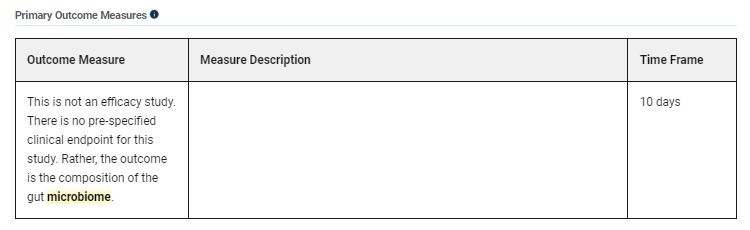

Here are the typical outcomes of microbiome trials (if you think I’m lying, go into clinicaltrials.gov, search for trials using microbiome as the “other terms” and diet as “the intervention”).

As I mentioned in this post, when you measure 100 outcomes in a study you’ll get about five which come back as having changed “significantly” - but each of these is likely to be a false positive. Our body’s cells, hormones and enzymes etc are going up and down and changing all the time so if you measure lots of them, you’ll always find a few that have…. changed. And unless you design your study properly you’ll have no ides if these changes are random or caused by your intervention.

And the same is true of the microbiome, which is comprised of trillions of cells. Even if you conservatively churn a few thousand variables you measure from the microbiome (see figure below) through statistical software? You’re gonna get LOADS of “significant” changes. What does it mean? We have no idea.

You are 100% certain to get “significant” (and publishable) results from your intervention if you lower your scientific standards as subterranean as “the microbiome is going to change”. NATURE METABOLISM HERE I COME.

I don’t think the microbiome is irrelevant.

When Jeff Gordon’s group put the microbiota of conventionally-raised mice into germ-free mice (mice with a sterile colon), and found the latter gained body fat and developed insulin resistance within two weeks, it clearly showed that the microbiome plays a critical role in metabolism. But the microbiome is basically an organ. If I took any organ from one person or creature and gave it to another I would expect it to have profound effects on their health. But talking about how the diet can affect the function of an organ is very different from an organ transplant! And the most we know is that a high-fibre, unprocessed diet is the best thing you can do for your microbiome and metabolic health.

Right now, the rest is just noise and marketing.

*I think this type of study is very useful. It was an exploratory study but this type of robust study design (transferring the baseline and post-sweetener microbiome from people who had a negative response to rodents) is a good way to establish causality. Whether any of these changes are clinically significant I think is in debate but I want to highlight that there are some researchers who are making a difference.

**There are some groups like this one who are working to improve the quality of this data - but it still doesn’t mean we’re going to get this precision down to “specific species we can replace to fix diseases” anytime soon.

Disclaimer

As a dietitian, and not a medical doctor, I am not qualified to diagnose any health conditions.

I work in microbiome research. The nuance which is often missed is that most studies looking at microbial community composition (ie looking at DNA and seeing what bugs are there and in what relative abundance) are completely missing the functional aspects of microbes (ie what are those bacteria doing, what genes are they switching on/off, what proteins/metabolites are present). We know that bacterial communities are very fluid - they share genetic material, easily mutate, share nutrients and interact with the host in a complex manner etc. For example, two people could have similar levels of a pathogenic gut bacteria but only one be afflicted by disease due to functional differences. There’s a long way to go in this field and a lot to tease out.

A man called "Tim" loves to brag about his microbiome "score" on a certain podcast. Thank you for this post, it puts alot of what is said and written about into context.