What is prediabetes?

And why do we care about blood glucose being high?

I covered type 2 diabetes in the previous post. Let’s move onto prediabetes.

What is prediabetes?

Prediabetes is when blood glucose is higher than normal but not high enough to meet the threshold for type 2 diabetes diagnosis.

Other terms like “impaired fasting glucose”, “elevated fasting glucose”, “impaired glucose tolerance” may also be used to mean “prediabetes”, and we’ll discuss what they mean below.

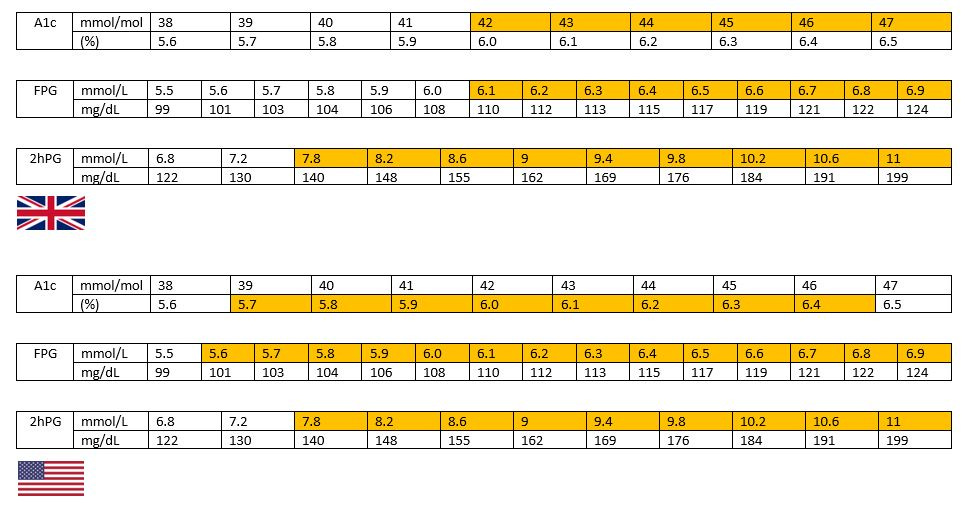

Here are the cut-offs for prediabetes:

Fasting glucose from 6.1 to 6.9 mmol/L (or 110 to 124 mg/dL) (we also call this impaired fasting glucose (IFG)).

In the USA, the cut off for impaired fasting glucose is 5.6mmol/L (100mg/dL).

2-hour glucose (taken 2 hours after a person consumes 75g glucose under standardised conditions) from 7.8 to 11.0 mmol/L (or 140 to 198 mg/dL). (We also call this impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)).

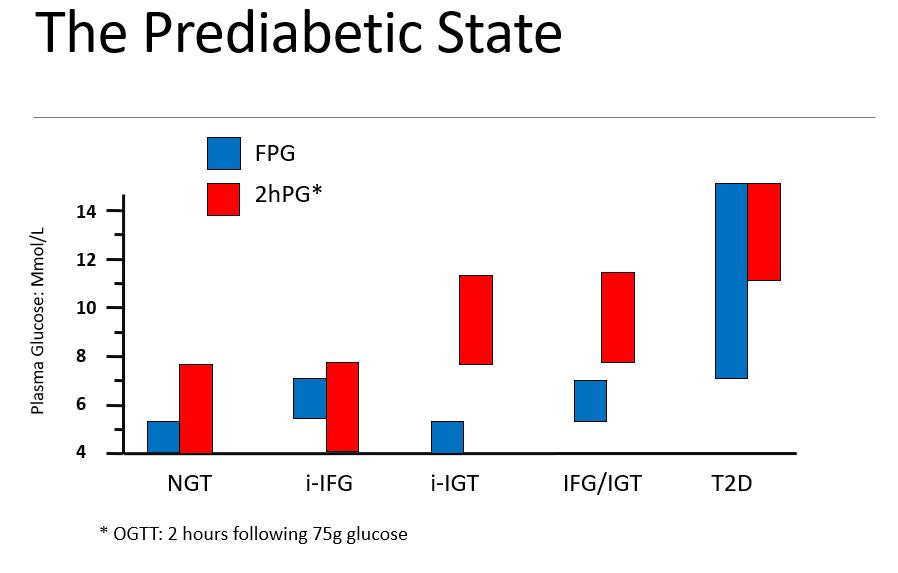

People can have elevated fasting glucose, elevated 2-hour glucose, or both.

The below image also gives you an indication of how different isolated-IFG (when only fasting glucose is elevated) and isolated-IGT (when only 2-hour glucose is elevated) are in terms of when glucose is high.

The pathophysiology of elevated fasting and elevated post-prandial is also different.

People with i-IFG have liver insulin resistance, but usually about normal muscle insulin sensitivity.

People with i-IGT have peripheral insulin resistance but normal or only mildly impaired hepatic insulin sensitivity.

Why we do we care about prediabetes?

We care because it can (but not always) indicate a person has a high risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the near future. In addition, there is also some evidence that many of the complications of type 2 diabetes (such as macrovascular disease) also apply in prediabetes. In other words, you don’t have to have diabetes to develop some of the complications of diabetes.

Prediabetes and risk of developing type 2 diabetes:

It’s worth bearing in mind that the risk of developing type 2 diabetes goes up as we age. Probably because a decline in beta-cell function appears to be a natural part of aging. In fact, while about two thirds of the reason behind the current type 2 diabetes pandemic is lifestyle-driven, about one third is aging. So when we think about risk remember that if everyone lived to 200 most of us would probably get type 2 diabetes.

At the individual level, I think most people want to know if they’ll develop type 2 diabetes in the near future (eg, in 5 to 15 years, depending on their current age). And luckily that’s what lots of studies have looked at.

The annual incidence rate of developing type 2 diabetes if you have the different types of prediabetes is about:

6-9% (i-IFG)

4-6% (i-IGT)

15-19% (IFG/IGT)

But bear in mind, these are population-based estimates. (And the i-IFG one is really controversial, because people with i-IFG based on the US (ADA) criteria have a much lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared to people with i-IFG based on the UK (WHO criteria). The relationship between having “prediabetes” and risk of developing type 2 diabetes also varies based on a lot of factors like age, family history of T2D, BMI, lifestyle and more.

Prevention

The great news is that people can prevent or delay the development of type 2 diabetes with very simple and modest lifestyle changes. I’ve written some notes here on what to if your glucose is high (or you’re worried your glucose might be high) but doing more physical activity and losing a small amount of weight if clinically indicated (as little as 2-3kg can help a lot) has a major impact on prevention.

Prediabetes and macrovascular disease:

There is concern that the risk of developing CVD and other diseases is elevated in prediabetes. However, note that these findings are not universal, and it’s not clear cut. This meta-analysis found that in people without prediabetes having an HbA1c between 5-0% and 6.0% seemed to be optimal in terms of CV outcomes and mortality - but it had quite a few limitations, and if you read through the paper you can see the uncertainty there is.

Since the pathophysiology of prediabetes is so distinct, it’s reasonable to think that perhaps some of the conflicting data could be due to some people having an HbA1c largely driven by elevated fasting glucose, and others having a high HbA1c driven by post-prandial hyperglycaemia. The data is not completely clear, but in general it looks like the relationship between elevated post-load glucose and macrovascular disease risk is greater than that for elevated fasting glucose and macrovascular disease risk.

But it’s worth remembering: 1) we don’t have a ton of data points on this (because OGTTs are not done that often, especially in cohort studies), and 2) the impact of elevated post-load glucose on macrovascular disease might depend on how often a person eats, what they eat, and how much they eat, because each of these factors will influence overall exposure of tissues to elevated glucose.

Prediabetes vs “Glucose Spikes”

So how is all this relevant to CGM use in people without prediabetes or type 2 diabetes? Well, let me just put what hyperglycaemia in prediabetes (I’ll do IFG/IGT) looks like vs “glucose spikes” in normoglycaemia:

The key in prediabetes is how prolonged the glycaemic exposure is. If you have i-IFG, your glucose has been elevated for many hours during the night. Likewise in i-IGT you have a glucose that runs about 7.8mmol/L for probably at least a good hour and a half, maybe more, and depending on how many meals/snacks a person eats, this could mean 10-12 hours per day with a glucose above this concentration. If you have IFG/IGT, your glucose may be elevated for more than half the day.

The second point is what is CAUSING the elevation in glucose - as I describe in the following posts it is pathological changes in underlying tissue and organ metabolism that are leading to these prolonged elevations in glucose. This has absolute nothing to do with the elevation in blood glucose which arises from the consumption of carbohydrate.

Thank you for this and other posts today. Well worth the wait I have questions of course.

I have A1C of 5.8 gradually rising over the last few years. First, my yearly panel measures A1C and fasting glucose but not postprandial glucose. Is the latter necessary or helpful?

I am 60. If age alone causes beta cell malfunction, then what about aging is responsible? Is it overwork from having a high carb diet? My spouse who is similar in age and background and diet also has A1C like mine.

Since I have a CGM, I can see that many of my glucose peaks are like the red curves in your slide- prolonged. But when I eat a high carb meal then I get a quick high peak and prompt return like the green lines, but sometimes dipping low as well. I have been trying to avoid those high peak meals because that’s what I have been instructed to do by the educator.