A new high-profile study is out, and its dissemination is being bankrolled by the marketing team of a multi-million dollar private company.

What is Zoe?

For readers who aren't aware, Zoe is probably the largest personalised nutrition company in the UK, and is also unique in terms of its academic credentials.

Many of the research team and company members work at some of the world’s top universities, and they lean HEAVILY on their scientific credentials in their marketing.

What makes Zoe special?

They have spent about 4 years doing some pretty cool exploratory science - looking at the gut microbiome, and glycaemic and lipid responses to meals between people.

Their big USP is that people have distinct metabolic responses to food - differences which are driven largely by their microbiome - and that we need diets personalised to this individual biology to get better health.

There’s no evidence behind this claim, but it’s a seriously great hypothesis - and all it needed was Zoe to do a trial to test it.

And yes! The much heralded Zoe METHOD trial is out!

BUT WAIT.

The Zoe Method trial did not test whether their novel “biologically-driven” personalised advice was better* than generic healthy eating advice.

They tested whether the Zoe programme, with all its support, self-monitoring, education, and other bells and whistles was better* than a leaflet on generic healthy eating advice and a few emails.

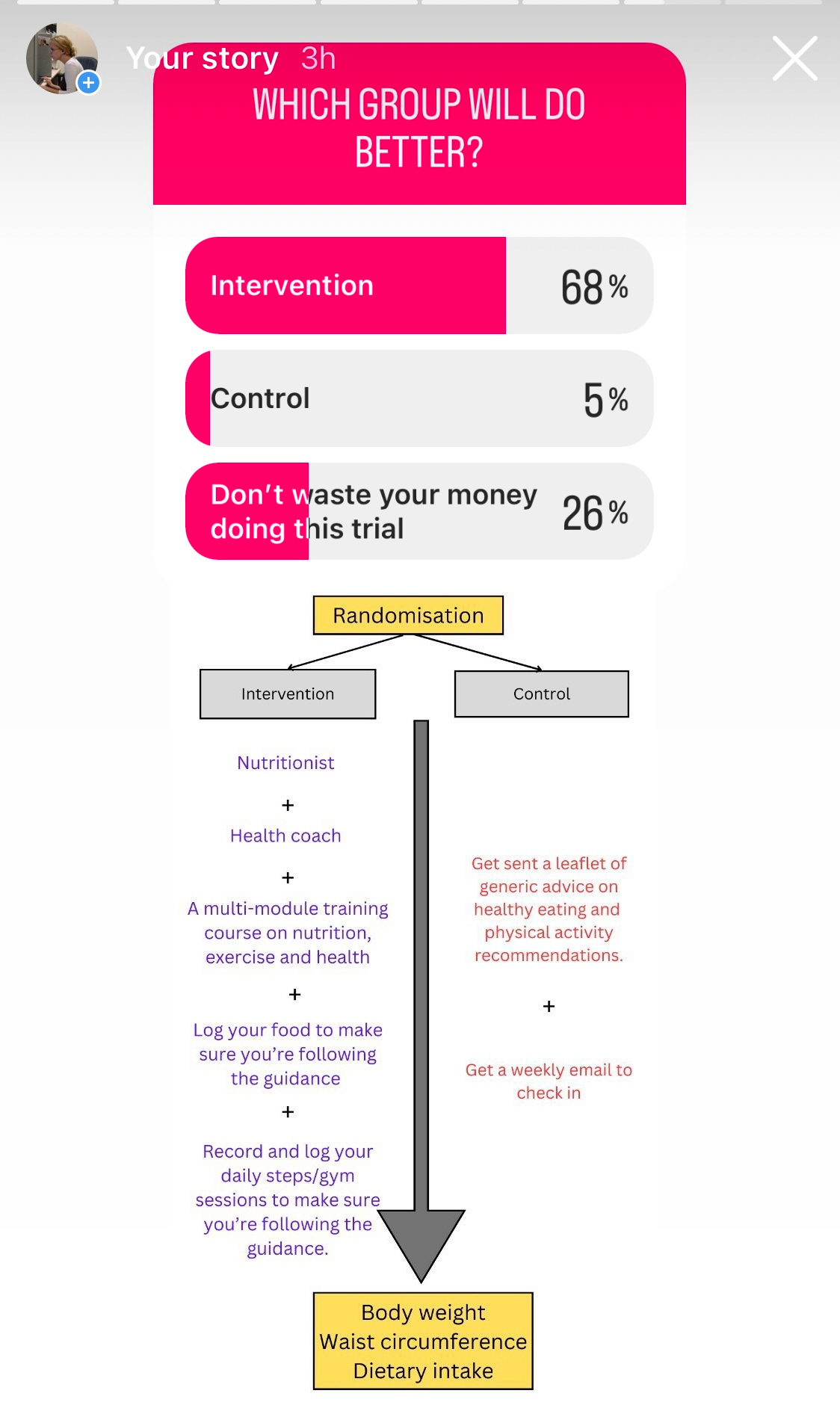

I did a poll on my Instagram stories, and basically asked whether a really intensive program would get better outcomes than a much less intensive program:

Bottom Line

If you don't want to read anymore, my interpretation of the study and its marketing is this:

Imagine if a pharma company tested their new drug in an unblinded clinical trial, gave the group who received the drug a personal trainer and nutritionist, sent the control group a leaflet and then tried to claim the drug “worked”.

And imagine if that pharma company - when asked why they didn’t design the study to test the efficacy of the drug said - “for us it’s not just about the drug, it’s the whole package of care”.

(Um, it's really not is it? In any case, if you’ve spent £££££££££££££££££££££££ on developing a drug/biologically-driven nutrition programme, wouldn’t you want to know whether it……………. works?)

In-depth critique of the trial

Why can’t this study design** tell us anything about whether the much-heralded biological personalisation had any effect?

Lack of blinding

The intervention group knew they were in the intervention because the study participants were not blinded. Why does this matter? Because people who know they are receiving the new cutting edge science-based programme are likely to believe they will feel better and get better outcomes. (We call this an expectation of efficacy, and it causes performance bias).

If people believe in the new “eat this carrot, apple and cauliflower because they will fix your microbiome which will fix your weight” programme they'll be more likely to eat that carrot, apple and cauliflower. They'll also probably be filled with hope and optimism, which are feelings generally associated with a new outlook on life including eating better and doing more exercise.

Meanwhile, the folks in the control group get a boring one-off leaflet that they've probably seen 1 million times before, and know they’re in the group that probably isn’t going to work.

And how do we know this design flaw influenced the outcome of this trial? Because participants in the Zoe group were already losing significantly more weight than the control before they received the results from their microbiome analysis etc.

They had loads of support in the intervention and very little in the control.

The intervention group received an ongoing behavioural programme during which they received frequent support and reminders of what they were supposed to be doing. We know that the more contact/reminders/nudges a programme has, the greater the likelihood that people will change their behaviour- like eating better, and doing more exercise.

For example, the intervention group were asked to input in real-time everything they ate on at least 4 occasions each month, but the control group did not have to do this.

Think about if a doctor or a dietician asks you to record everything you eat, as you are about to eat it. Would that make you pause when you go for that second cookie? Would it make you have a few more veggies than you usually do because you know someone is going to be reviewing what you ate? In that case you're not alone, because this is what most people do. In fact, the completion of a food diary can be thought of as “an intervention” in its own right.

The intervention arm also had to undergo the battery of extensive testing that the Zoe programme requires. This type of extensive testing 1) serves as a reminder to people that “you’re being “watched”” (Hawthorne effect: when people are being “watched” they change their behaviour), and also a reminder that “you’re in the cutting-edge group that’s getting this awesome new scientific programme”. Both of which will serve as prompts to keep eating more veg and less junk.

The intervention arm also had to wear a continuous glucose monitor for four of the 18 weeks. It’s unclear what specific effect wearing a CGM has on eating behaviour, but in general it’s probably a bit of a reinforcement like logging food intake “remember you’re being monitored”.

The intervention arm also received a personal walk through with a Zoe staff member once they got their personalised results at week 6.

The intervention arm also received interactive ‘lessons’ as part of a program of learning about nutrition including the importance of eating more fibre, more plants and eating less processed foods.

Once they got their personalised scores, they got a series of lessons “administered in the app for 12 weeks during which participants were taught how to engage with and adhere to their personalized plan”.

The intervention group also had to spend one hour EVERY DAY logging their food to see how close they were getting to personalised recommendations***.

It’s a LOT.

By contrast, the control group received generic information in the form of a leaflet. The manuscript says that weekly email contact was made, and that people could also view the leaflet as a video format.

The study design basically looked like this:

The fact Zoe designed the trial this way is craziness to me

Zoe have spent five years and tens of millions of pounds on all of their exploratory science. Their initial studies, where they did cool large-scale characterisation of people’s microbiomes and glucose and lipid responses to meals are actually really interesting.

Interesting doesn't mean clinically relevant though, and most people in the nutrition science field from my experience are pretty sceptical that these small interpersonal differences actually mean anything.

But hell, this is why we do clinical trials isn't it? To see whether this type of early exploratory science leads to genuinely new innovations.

Yet instead of running a trial that could've answered this genuinely important scientific question (How? Double-blinding, sham-testing, and equipoise of support) , Zoe have designed a trial in which the Zoe programme was always going to do better than the “control”.

What do I think is going on here? (Sorry, this bit is harsh…..).

Zoe has received over £100M of investment and is now stuck in a tough place: how to stand out and become profitable in a crowded field of dietary behavioural apps. Their app helps people eat more fruit and veg? Great, but many nutrition apps do this at 20% of the cost.

Sadly– as the CSO of Zoe repeatedly points out – there is no incentive for a food company or a personalised nutrition company to design a trial that doesn’t show their product off in the best light****.

I don't wanna use the T word, but this reminds me a little bit of the Theranos story: “listen our new amazing innovation works, it definitely works. We can't show it yet with proper data, but here let us feed you some bullshit, that will get investors (none of whom are actual scientists (Eli Manning, Stephen Bartlett)) to give us more money cos we got it published in Nature Medicine, we’ll keep refining our algorithms and we promise we’ll show you it works real soon”.

Maybe they will, and I'll look like an idiot, ha ha.

But for now, what can we say about a dietary intervention which costs ~£700 a year? It's better than a leaflet.

*this is actually going to get worse because they had two primary outcomes and they found no difference in one of them.

**I’m sorry to the investigators but I think the entire study design was a complete mess (they had two primary outcomes; they didn’t measure physical activity; they had way too little support in the control group but not limited enough to represent “usual care” etc) but I have limited my comments to the most prominent ones which meant the study tells us… nothing new.

***I wasn’t sure about the daily food logging, but yes confirmed here: https://zoe.com/method-study/signup

****I actually don’t think this is wholly true: The relationship between funding and the quality of a trial is complex, and I don’t buy the idea that industry funding necessarily means a poor quality trial. For example, DayTwo - another personalised nutrition company - have tested their algorithm in really well-designed trials - in one of them, the algorithm had no benefit and they published the findings anyway.

It doesn't take an hour to fill in the food questionnaire on the app. About 10 minutes max. You've taken that too literally.

And they are testing their method against, say, typical NHS nutritional advice and support, which is negligible.

So your criticism is flawed here. They are setting out to prove their own product works, which is exactly what you describe in your post. They offer coaching, food tips, customer support and testing to those who can afford it. Roughly about the price of a gym membership (which is arguably a waste of time for many people). Can't see why they would be trialling something else. What are you suggesting?

Maybe the NHS or the government could provide more nutritional support to the nation and improve overall help instead?

The CGM, blood tests and gut tests are only relevant for that moment when they are taken, but there must be something said for the educational benefit. They make you think about your body, what you are eating and what is going on inside you. That allows you to make better informed decisions about your own diet and fitness.

Zoe has managed to push healthy eating of whole foods into the mainstream media in a way that was not happening before. They should be congratulated for that.

You seem to have a total downer on them and I've not seen anything constructive in your posts about an alternative method. Maybe I'm wrong though, so a point in the right direction would be helpful.

In short, they had a 'control group' that didn't control all the variables, including some that we know can have an impact on changing health behaviours; giving it no credibility as a study or proof of anything.

I wish I'd known that before I spent hundreds on ZOE.

At the heart of their argument and rationale is a circle: between the foods you eat, the gut bugs you have, and your state of health. Their large PREDICT study showed a correlation between these. And that was interesting and I was very keen to get on the programme.

But where does the causality lie? If you eat healthy foods, you will encourage health-associated gut bugs, and you will also score better on many health markers. But are you scoring better on health because you ate the healthy foods or because you have healthy bugs? - It might not matter; but then you don't need to spend £300+ pounds to learn that eating healthy foods correlates with being healthy.

Their second important claim is that their testing gives you your unique profile and therefore unique advice, on presumably a unique diet that will make YOU healthy. - But if they claim that there are 50 'good bugs' and these good bugs are good for everybody, and we know what these microbes tastes and preferences are in foods; then even if our microbiome is unique in what we actually have now, the bugs that would be good for us are the same for everybody and therefore the foods we should eat to encourage them should be the same for everybody. - I wish I'd spotted this logical flaw earlier.

A wise, wry friend said, when I explained it to her, 'Yeah, but they're never going to tell you your unique profile means doughnuts are good for you and kale is bad.' I thought at the time she was missing the point, but she was hitting the nail on the head.

I, my husband, my sister, my best friend all did it at the same time. Vegetables and nuts were good for all of us and our gut bugs; ultra-processed foods, meat, refined starches, sugars, saturated fat were bad for us and our bugs. We didn't vary much. And overall I'd say the only variability that might make a difference is not about the gut bugs that is their big selling point; - it's how well your body deals with sugar and fat, and you can get tests for that from your GP. Your GP wouldn't (I assume) have the data to tell you how you score against ZOE's cohort, but I don't really need to know I'm at x% - I need to know if I have to change my diet based on standard, well-known parameters for being pre-diabetic etc.

While I was enrolled, I asked multiple times about the specificity of the food they were giving me in the app as 'gut boosters' and bad foods for MY UNIQUE gut bugs - since they are very specific. For example, apparently my ten worst foods for gut-bugs included chicken sausages, chicken soup, chicken pies. - Did that mean that pork sausages and beef pies or soups were okay? Probably not, as chicken was had a higher (good) score than pork or beef. Were these just generic stand-ins to say 'don't eat too many ultra-processed foods or meat'? - I didn't need to pay over £300 for that advice. So I asked how they determined which foods were good/bad for my microbiome and they never seemed to understand my exact question and just referred to the PREDICT study as having - allegedly - shown which foods the good gut bugs like.

I read that study multiple times; but it only shows you a correlation between certain microbes and a very broad categories of foods: e.g. 'vegetables', 'dairy', 'meat' and so on. If you read the study, which is free and in the public domain, then you will see that you need to eat vegetables, whole grains [etc] and less processed food, meat, alcohol [etc]... what is already recognised by most as a high-quality diet in order to have healthy gut bugs. I never found out what evidence they had for giving specific foods, vegetables or fruits higher or lower numerical scores, and the help staff were unable to explain.

They seem to trumpet a lot that they know exactly which foods encourage which microbes, and I do really fault them on this as a serious, culpable bit of misinformation or exaggeration; I can't see any published evidence for this. Not beyond the generic 'these microbes show up for vegetables, and those show up for meat. And the people with those microbes have higher cholesterol.' (But is that down to the microbes or the meat?

I wonder if they have *ever* published any data to show how diverse their dietary recommendations are between individuals. Now THAT would be an interesting study. Does anyone have a unique profile telling them doughnuts are good for their unique microbiome and kale is bad?