Proponents of CGMs often claim that they can give people insight into foods that people can and cannot tolerate. “Eat for your unique metabolism!”. “Understand how food affects YOUR body!” - if your glucose goes up after one type of food - then you know to avoid it, right?

The problem with this approach is that it assumes that glucose excursion following any given meal is directly due to whatever that person ate AT that meal. And this isn’t true.

A variety of things can affect the glucose response to a given meal that have nothing to do with what you actually ate at that meal:

The second meal effect

Physiological changes which have developed as a response to a low-carb diet.

Stress

Sleep

Menstrual cycle

The exercise you did in the days or hours preceding the meal.

Other things (yes I got bored at this point haha).

The second meal effect

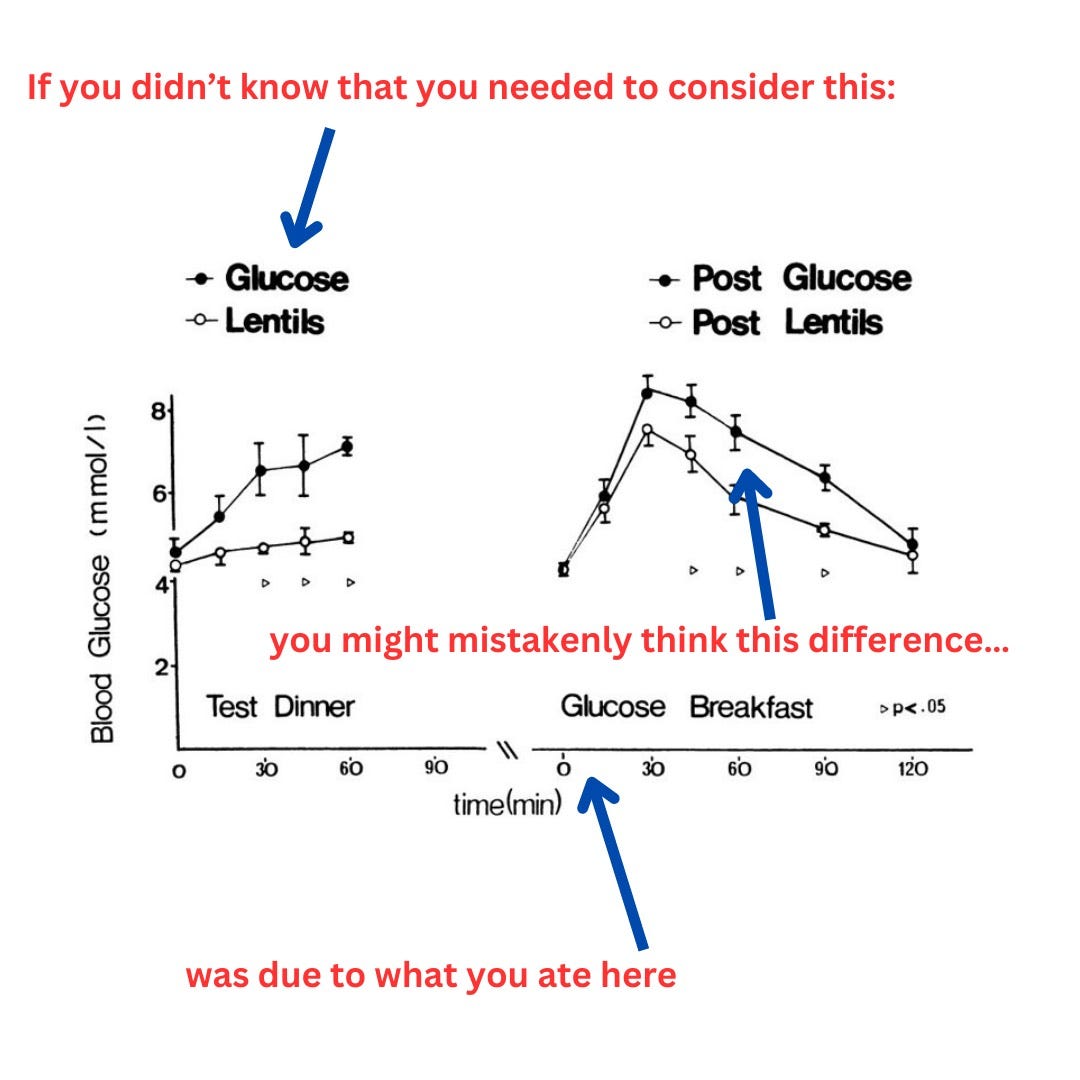

This is a well documented physiological phenomenon whereby the food you eat for your current meal influences the postprandial glycemic response at the next meal. As far as I have read, this phenomenon occurs with wholegrains, legumes and other high-fibre carbohydrates. And by the way, the effect size can be significant. In this paper - there was a ~2mmol/L difference at most time point in the glucose response to an identical carbohydrate load, if the previous meal contains lentils as opposed to bread.

Conversely, having a dose of whey protein the night before a standard meal tolerance tests worsens the glucose response to the meal tolerance test. (The difference was about 0.6mmol/L but still, this was significantly different between the groups and is within the range of “distinct” glucose responses claimed by “personalised nutrition”). The amount of fat consumed at breakfast can worsen the glucose response to lunch.

Physiological changes which have developed as a response to carbohydrate restriction.

Going low-carb can induce physiological changes (probably a reduction in insulin secretory response and development of some kind of insulin resistance) which means that when that person next eats some carb they’ll have an exaggerated glycaemic response.

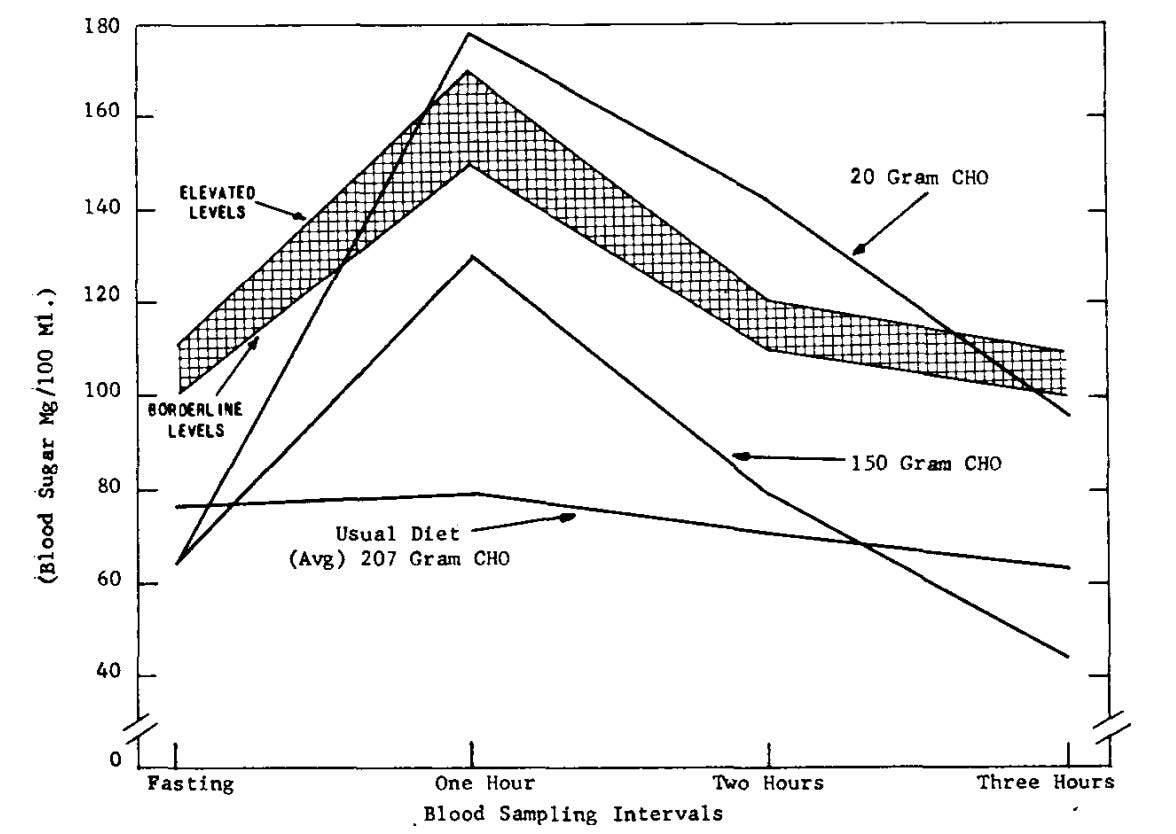

This phenomenon has been known about since the 40s, and is the reason an OGTT test should be administered following standardised carbohydrate intake for 3 days prior to the test. Healthy males and females who take an OGTT after 5 days of 20g carb per day show up (falsely) as having impaired glucose tolerance (yes, prediabetes!!!)

When people are not aware of this phenomenon it can give them real anxiety and a fear they they “cannot tolerate” carbs and should always avoid them. For example, I have had patients who went low-carb and then wanted to see if they could introduce foods like lentils or some fruit. But what happened when they tried the lentils after a period of low-carb? They got a massive response to the lentils!! My advice is always give your transcription factors/enzymes/hormones etc time to up- or down-regulate/increase production etc so your body can respond appropriately to any new foods/diet.

Also note that simply having a low-carb meal the night prior to an OGTT (and presumably any significant carb load) causes an exaggerated glycaemic response to the OGTT compared to a higher carb evening meal even if the rest of their meals that day were 60% carb - this might be due to the second meal effect. But the point remains the same - the glycaemic response to the meal you are currently eating is influenced by multiple factors which have nothing to do with what’s in that meal.

Stress

Lots of people are aware that stress can influence your blood glucose levels, but may not be aware of just how much. The relationship between stress and glucose homeostasis is complex, but cortisol seems to play an important role, and acute stress increases cortisol. (Though let me add this area of endocrinology is not my area of expertise so I will tread lightly here!)

Undergoing a dental procedure increases cortisol and glucose in people with type 2 diabetes.

Acute mental stress in people with type 1 diabetes appears to prolong post-prandial hyperglycaemia potentially through an increase in insulin resistance.

In this very moving (and tough to read) study in refugees from the Bosnian war, acute stress causes a rise in the peak glucose of >1mmol/L (>20mg/dL).

Now of course, these are quite extreme examples of stress, but lots of people deal with numerous challenges in their daily lives - family sickness, financial worries, job-related stress. And all of these things could influence your glycaemic control.

For example, a stress test which involves a 5 minute talk and having to solve a maths problem in front of an audience caused an increase of ~1.5mmol/L (27mg/dL) pretty consistently throughout the post-prandial compared the control (no stress) condition. Again, a clinically significant difference in glucose excursions to a meal which have nothing to do with what’s in that meal.

Sleep

This is another factor that people are increasingly aware of. Sleep deprivation and sleep disturbances influence glucose regulatory mechanisms, as shown here and here and here and here. Eating at irregular times and out of whack with your circadian rhythms also alters your blood glucose control.

I won’t go too much into this one as I think this is mostly widely known, but in healthy young males who undergo partial sleep deprivation (4 hours sleep a night), their glucose response at each interval to a standard breakfast is on average 0.8mmol/L higher than when they sleep fully.

Again, clinically significant difference in glucose excursion - nothing to do with what they ate at the meal.

Menstrual cycle

Women might have decreased glucose tolerance in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, and this has been shown in quite a few studies here, here and here.

However, other investigators have not replicated these findings. Whether this is due to sample size, type of methodology used to test glucose and insulin dynamics, or potentially inherent inter-person variability in female hormones I don’t know.

Nevertheless, it’s possible a person eating a banana during the last 2 weeks of their menstrual cycle will have a higher glycaemic response compared to during the first two weeks.

The exercise you did in the days or hours preceding the meal.

Most people know that regularly engaging in physical activity can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes. What people might not know is the acute effect a single bout of physical activity can have on your glucose.

Your glucose response to a food will be higher if you eat it immediately following a bout of intense exercise, versus after rest. This period of elevated glucose probably lasts about one hour. However, once the immediate post exercise period is over - the acute exercise bout actually makes people more insulin sensitive (and with better glucose tolerance) up to 3 days after the exercise compared their usual baseline.

If you look at the figure above, you see the degree of glucose tolerance appears to worsen (it’s basically just reverting back to baseline) from days 1 and 3. Day 2 is not shown but it might well be somewhere between day 1 and 3. Let’s imagine you eat a bowl of oats with whole milk on on day 1 - you’ll have a glucose response that looks fairly low. Now let’s imagine you run out of whole milk on day 5 and have semi-skimmed milk with your oats - you’ll get a larger rise in glucose. You might think this is due to the type of milk and resolve to have whole milk to better control your glucose. But hopefully you can see with this example the change in glucose tolerance may well be due to the exercise you did - and the milk has nothing to do with it.

And further supporting the complexity of factors that can influence the glucose response to a meal, but are not caused by food consumed at that meal, is the observation that glucose tolerance following exercise might be worsened by prior meal ingestion!

Other things

Getting really cold (to the point where you’re shivering for an hour) might decrease glucose tolerance. Alcohol consumption might influence the glucose response to a meal, depending on when the alcohol is consumed in relation to the meal.

Summary

I hope I have convinced you that loads of things can influence your glucose response to a meal which have absolutely nothing to do with what’s in that meal. And this is why it’s so challenging to tell - in uncontrolled conditions - what an individual food does to blood glucose. Because so many variables are simultaneously affecting the blood glucose response.

And just a note to say I am very, very skeptical that there are meaningful inter-personal differences between people’s glucose responses to food. I’ll expand more on this in later posts.

Hello

Appreciate for your informative articles

I can't see reference for this paragraph.

Your glucose response to a food will be higher if you eat it immediately following a bout of intense exercise, versus after rest. This period of elevated glucose probably lasts about one hour. However, once the immediate post exercise period is over - the acute exercise bout actually makes people more insulin sensitive (and with better glucose tolerance) up to 3 days after the exercise compared their usual baseline.

Would you please find out the reference?

So many questions were answered in this series of posts. Great stuff! Thanks! (Nice calling out those scammers selling CGMs to fitness people. I was one of those fools buying:))